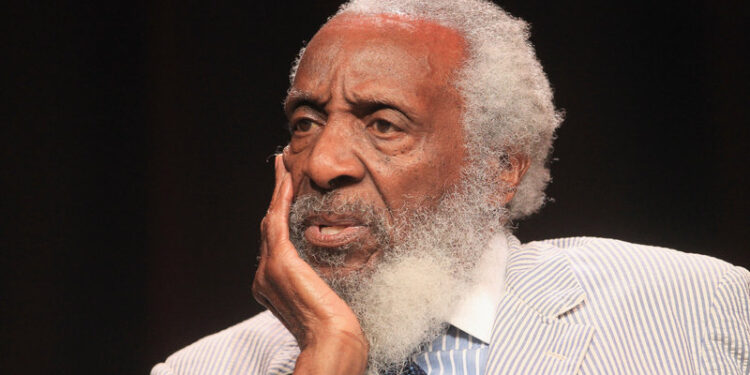

Dick Gregory, the comedian and civil rights crusader, died Saturday. He was 84.

His family announced the news on his public Facebook page.

“It is with enormous sadness that the Gregory family confirms that their father, comedic legend and civil rights activist Mr. Dick Gregory departed this earth tonight in Washington, DC,” his son Christian Gregory said in the post. “The family appreciates the outpouring of support and love and respectfully asks for their privacy as they grieve during this very difficult time. More details will be released over the next few days.”

According to The Associated Press, Gregory, who was recently in and out of the hospital, died following a severe bacterial infection. NPR has not independently confirmed the cause of death.

Gregory gained attention as a comedian in the early 1960s, and was the first black comedian to widely win plaudits from white audiences. Darryl Littleton, author of the book Black Comedians on Black Comedy, told NPR in 2009 that Gregory broke barriers with his appearances on television, just by sitting down:

“Dick Gregory is the first to recognized — and he’ll say it — the first black comedian to be able to stand flat-footed, and just delivered comedy. You had other comedians back then but they always had to do a little song or a dance or whatever, Sammy Davis had to dance and sing, and then tell jokes. Same with Pearl Bailey and some of the other comedians. But Dick Gregory was able to grow on television, sit down on the Jack Paar show — and sit on the couch and actually have a discussion, and that it never happened in the history of television.”

Gregory “opened the door” for Bill Cosby to rise to fame, Littleton said.

He was noted for his political and social activism, beginning in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. He attended the historic 1963 March on Washington. Forty years later, Gregory told Tavis Smiley on NPR about his experience at the march, describing it as “joy. It was festivity, and as far as the human eye could see.”

Gregory talked in 2003 about his experience trying to integrate a restaurant in Mississippi before the march, showing he could inject some humor into a serious story:

“We tried to integrate a restaurant, and they said, `We don’t serve colored folk here,’ and I said, `Well, I don’t eat colored folk nowhere. Bring me some pork chops.’ And then Ku Klux Klan come in, and the woman say, `We don’t have no pork chops,’ so I say, `Well, bring me a whole fried chicken.’ And then the Klan walked up to me when they put that whole fried chicken in front of me, and they say, `Whatever you do to that chicken, boy, we’re going to do to you.’ So I opened up its legs and kissed it in the rump and tell you all, `Be my guest.’ ”

He was direct in his language about race. He co-wrote with Robert Lipsyte the book nigger: An Autobiography — the “n” is lowercase — in 1964. Gregory explained to NPR why he chose that title:

“So this word ‘nigger’ was one of the most well-used words in America, particularly among black folks. And I said, `Well, let’s pull it out the closet. Let’s lay it out here. Let’s deal with it. Let’s dissect it.’ Now the problem I have today is people call it the N-word. It should never be called the N-word. You see, how do you talk about a swastika by using another term?”

Gregory called the U.S. “the number-one most racist system on the planet. … And I hope that America is willing to take this shoe of racism off and deal with racism and deal with sexism.”

He ran for mayor of Chicago in 1967 and ran for president in 1968 under the Freedom and Peace Party. He was on the ballot in eight states and got 47,133 votes, as Ken Rudin wrote for NPR.

Hunger strikes were a frequent activist tool for Gregory. He told Juan Williams on Talk of the Nation that he went without solid food for two and a half years to protest the war in Vietnam.

At one point, he said he weighed 365 pounds. But he lost a lot of weight fasting to protest the war. “I went on a fast, 40 days of water. Forty days of fruit juice. Forty days of fruit. And then 40 days of water again,” Gregory told NPR.

In 2000, Gregory went on a hunger strike to protest police brutality, long before the current wave of activism.

Gregory promoted some conspiracy theories, telling NPR in 2005 about conspiracies involving the death of Princess Diana and the Sept. 11 attacks. “The FBI and the CIA is probably the two most evil entities that ever existed in the history of the planet,” Gregory told Ed Gordon on News & Notes.

He was also an inspired health guru, who doled out advice to many for better living, including celebrities like Michael Jackson, whom he advised during the singer’s trial.

The musician Questlove paid tribute to Gregory’s healthful influence on Instagram, as “one of the first major black figures I saw advocating for a healthier lifestyle for black folks that were caught on unhealthy choices we’ve made in the name of cheaper survival options,” he wrote.

Gregory joked about getting old with Tavis Smiley in 2002:

“Here’s how you can tell when you’re getting old. When someone compliment those beautiful alligator shoes you’re wearing and you’re barefooted. … Or when your lady or man hollers downstairs, `Dear, run upstairs and let’s have some sex,’ and you yell back, `You know I can just do one or the other,’ then you kind of be in trouble, you know.”

Gregory was married for more than 50 years and had 10 children. His daughter Ayanna Gregory released a song called “A Ballad For My Father” in 2007. She told NPR that her father was gone from home often, but it was because “human rights became his life.”

She sang: “As a little girl, I didn’t know what you meant to this world. If I had a dime for every time somebody told me it’s to save their lives and changed their minds. You planted seeds so long ago deep in me so I would grow.”

Gregory mused about death in 2006, when talking with Ed Gordon about the passing at the time of Coretta Scott King:

“Let me just say this, whenever you die from this planet, I feel you go some place, and my trip going to be so long to wherever I go, I got instructions from my wife to put on a couple of backpacks.”

npr.com