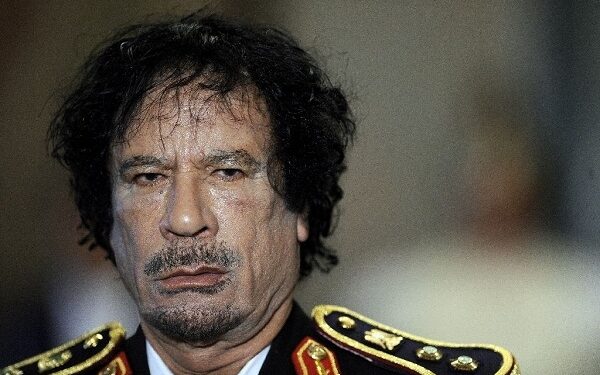

Five years after an uprising killed Libya’s Moamer Kadhafi, residents in the chaos-wracked country’s capital joke they have grown to miss the longtime dictator as the frustrations of daily life mount.

Those living in the capital say they are exhausted by power cuts, price hikes and a lack of cash flow as rival authorities and militias battle for control of the fragmented oil-rich country.

“I hate to say it but our life was better under the previous regime,” says Fayza al-Naas, a 42-year-old pharmacist, referring to Kadhafi’s more than four decades of rule.

Today, “we wait for hours outside banks to beg cashiers to give us some of our own money. Everything is three times more expensive.”

A UN-backed unity government has struggled to assert its authority nationwide since arriving in Tripoli in March, with a rival parliament in the country’s far east refusing to cede power to it.

On Friday it suffered a new blow when a rival seized key offices in the capital and proclaimed the reinstatement of a third administration previously based in Tripoli.

The turmoil after Kadhafi’s 2011 fall has allowed the Islamic State jihadist group to gain a foothold on Europe’s doorstep after seizing the strongman’s hometown of Sirte in June last year.

Forces loyal to the unity government have for five months been fighting to expel the last jihadists from the former IS stronghold, with support from US air strikes since early August.

With the loyalists weakened by the anti-IS battle, forces led by a controversial field marshal last month seized key oil terminals to its east, allowing the National Oil Company to resume crude exports.

The eastern parliament has thrown its support behind Khalifa Haftar, who presents himself as Libya’s saviour in the face of a growing jihadist threat but is a hugely divisive figure.

– ‘Chaos or military rule’ –

While his army has ousted most jihadists from Benghazi, the birthplace of the 2011 uprising, his detractors accuse him of working towards the single goal of seizing power to establish a new military dictatorship.

“Libyans are forced to choose between two extremes: either chaos with militias and Islamist extremists as the dominant forces, or military rule,” said Libya analyst Mohamed Eljarh.

“No other convincing options are on offer,” added Eljarh, of the Rafik Hariri Centre for the Middle East.

Haftar’s forces have fought for more than two years to expel jihadists from second city Benghazi, while pro-GNA forces are caught up in fighting IS in Sirte.

According to Libya expert Mattia Toaldo, these rival forces might then want to extend their influence in other areas of the country and be met with tough local resistance.

“It is hard to think that the country will be stabilised any time soon,” said Toaldo.

“Libyans seem to have swapped a repressive centralised authoritarianism with a more decentralised and chaotic form of authoritarianism, be it under militias or under the rule of general Haftar.”

The persistent chaos has also enabled human traffickers to step up their lucrative trade in the Mediterranean nation, with hundreds of migrants dreaming of Europe drowning off the Libyan coast.

And Libya has been the launchpad of deadly attacks on holidaymakers in neighbouring Tunisia.

While some Libyans mourn an easier life under Kadhafi, others stress that the chaos in Libya springs from decades of mismanagement under the dictator.

“The struggles of Libyans today are the logical consequence of 42 years of systematic destruction and sabotage” by the state, said Abderrahman Abdelaal, 32, an architect unable to find work in his field.

War-weary Libyans miss life under Kadhafi

ADVERTISEMENT